1970

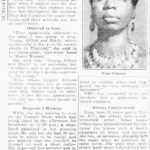

NINA SIMONE – HER STORM, HER SERENITY

There are those who say she’s evil and there have been times when members of her audiences turned the other way if this soulful sister stared them in the eye. But nobody’s going to dispute Nina Simone’s right to the title “High Priestess of Soul.”

Personal qualities are the artist. Nina Simone’s lyricism, her ability to create from and lose herself in moods are qualities integral to her art. Nina’s past is her music, too. The little girl who helped her Mama run revival meetings is there in the church piano she plays. So is the young woman who studied classical music at Juilliard, adding more technique to the gospel core. At times, dreams show up in the tender lyricism of her voice. On the other hand, the anger she feels keeps her honest – preventing that lyricism from becoming weak and insipid.

Nina started her career in 1953 as a supper club artist. Had she stopped at that, she would have been no more than a good artist. But not good enough to be the great singer she is today.

The year was 1963, when she was one of the first popular vocalists to wheel around and turn song into bitter protest. Medgar Evers was assassinated and Nina Simone added another dimension to her art. The message came out loud and strong in “Mississippi Goddam!”

From then on, her rendition of gospel and message blues (which are related) dominated her music. As she says on her recent LP Black Gold in the lead-in to the tune “To Be Young, Gifted and Black”: “It [the tune] is not primarily addressed to white people; though to does not put you down in any way. It simply ignores you. For my people need all the inspiration and love that they can get.”

And Nina has been out to give it. Although somewhat mellower now, she still rarely shelters her audiences. They have to know, if they listen, what it feels like to be Nina Simone.

The discovery of protest music is, properly speaking, a rediscovery. The message has been with us all along…in blues, in gospel music with its appeal for deliverance, in calypso with its sly satire. But Nina might have missed taking part in the rediscovery had she not gone back to reinvestigate and perpetuate her church roots. That was the trip (with a stopover at Juilliard) she had to take before she Ould become our strong spiritual force – our High Priestess of Soul.

Now she’s priestess and preacher. As her music continues to take expressive directions, Nina herself seems to be changing, although she’s definitely not to be messed with. Like most creative people, her source of sublimation is her craft. In an interview last year, as if referring to her own moods, she said: “Anything human can be felt through music.” Preach on. Sing on. We all feel and hear you, Nina.

Charles Hobson

RETURN OF THE QUEEN OF SHEBANG

The High Priestess of Soul, Nina Simone, lingers in the wings until her dashiki-clad band has tuned the house vibes to a special frequency of jungle jazz. Then the Queen of Shebang sweeps onstage in an exotic white gown, hair held high in an Afro topknot, a regal circlet of pearls girdling her forehead. Barely acknowledging the tinny rain of applause, she sits down at the grand piano, fingers a few delicately Debussyan chords and quietly intones, Black is the color of my true love’s hair.”

As her soft, hazy voice covers the mind like morning most, you think back to her first hit, I Loves You Porgy, with its gently caressing phrases, its air of still longing and erotic reverie. That performance summed up vocally the yearning of the late ’50s for something cool and beautiful and distant-like the silver-frosted notes of Miles Davis’ trumpet. Nina had been then the youngest and most promising of jazz singers, a tryo from Tryon, N.C., the sixth of eight children born to a handyman and a housekeeper who was also a Methodist minister.

Some local music teacher had recognized the child’s talent and gotten up a public fund to send the young Eunice Waymon to high school in Asheville and then way up north to Juilliard School of Music in New York.

Nina had been a piano student and had never thought about singing. Not till a hard-boiled nightclub owner in Atlantic City insisted that she sing as well as play for her supper did she being to pay attention to her voice. She discovered then – like many other classically trained black artist – that she had been better educated at home, down on the farm or in the ghetto, than at the conservatory. The moment she opened her mouth, she revealed herself as the bluesy disciple of Hazel Scott, Dinah Washington, and Billie Holiday.

Unlike those ladies, however, she found the market for her talents drying up as jazz, nightclubs and the cool world crumbled in the hot festive sunlight of the Woodstock Generation. She might have been defeated by this change of guard, the avant for arriere, but instead she was inspired. During the past few years, she has built her reputation so high as the toughest, funkiest, most hand-clappin’ ‘n finger-poppin’ of soul sisters that all she has to do is walk out on the stage of the Fillmore and the kids start taking the place apart.

The story of her turn-around comeback, the symbol of her invincible spirit and enormous youth appeal, is in her unforgettable interpretation of Ain’t Got No – I Got Life from Hair. As she begins to recite the endless catalog of things she (and the kids) ain’t got – “no job, no money, no home, no father, no mother, no pot, no wine, no tokens for the subway” – her hard, dark voice rises and falls with the imploring intonations of the blues. Building to the great turn in the tune, she suddenly swings around and proudly proclaims all the things she has got: health, smile, soul, sex, arms, hands, breasts and hair – her voice rising triumphantly on a hard-rocking, uh-uh! beat that carries her off in glory above the kids’ clapping, crowing, stomping, whistling ovation.

Nina Simone’s recent success hasn’t inspired her to correct any of the personality faults that have always made her hard to take off the record. She still pollutes the atmosphere with a hostility that owes less to her color than to the rasping edge on her pride. She still can’t make up her mind whether she’s a lofty lady like Miriam Makeba or a Gem-blade mama like Dinah Washington. She has still to learn that the humility of the true performer is based on the drastically simple fact that he owes his life to the public.

Albert Goldman

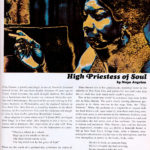

NINA SIMONE: HIGH PRIESTESS OF SOUL

MAYA ANGELOU

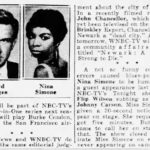

Nina Simone, a pianist and singer, is one of America’s foremost musical artists. She was born Eunice Waymon 35 years ago in Tryon, North Carolina, the sixth of eight children. Her father was a handyman and her mother an ordained Methodist minister and a housekeeper. She received her formal training at The Curtis Institute in Philadelphia, and the Juilliard School, in New York City. Miss Simone, a founding member of the Black Academy of Arts and Letters, lives with her eight year old daughter Lisa in New York’s suburban Westchester County.

Maya Angelou is a poet whose novel “I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings” is a best seller. Miss Angelou is also a dancer, an actress, and a producer. Her impressions of a visit with Nina Simone are recorded below. They are the impressions of a poet.

“There’s a wheel, in a wheel,

High up in the middle of the air.

The little wheel run by faith,

The big wheel run by the grace of God.”

These are the words of a spiritual that celebrates the vision of the prophet Ezekiel centuries ago. Today a profound artist, known to many as “the High Priestess of Soul,” informs us that her mother knew during pregnancy that she would deliver someone “very special.”

Slowly, softly, Nina Simone recalls her mother’s words: “It was the happiest nine months of my life. I was in another realm. I wasn’t here. I even knew your name.” A wheel holding a wheel, high up in the middle of the air.

Nina Simone sites in her comfortable, rambling home in the suburbs of New York City, and pushes her textured voice into the air while her dark hands make explicit gestures.

Few of her ardent fans would be convinced that there is this side to Nina Simone. The quiet, slowly moving afternoon personality is in direct contrast to the stage Nina, the “High Priestess.” When she performs in a nightclub or concert hall, her back forms a soft, open letter C; then those same long arms, which now move in slow motion in the afternoon shadows, seem to plunge beneath the wood and ivory of the piano to reach and manipulate the raw nerve ends of her audience. The response is instant and automatic. Nina Simone plays and her listeners are hypnotized, whether they are 20,000 at Randalls Island or 500 at New York City’s Village Gate. After a Simone, tone-setting introduction she tilts her face to the microphone, and the very atmosphere is jarred by the husky, dusky voice:

My skin is black, my arms are long.

My hair is wooly, my back is strong.

Strong enough to take the pain

Inflicted again and again.

What do they call me?

My name is Aunt Sarah.

My skin is yellow, my hair is long;

Between two worlds, I do belong.

My father was rich and white,

He forced my mother late one night.

What do they call me?

My name is “Safronia.”

My skin is tan, my hair is fine,

My hips invite you, my mouth like wine.

Whose little girl am I?

Anyone who has money to buy.

What do they call me?

My name is “Sweet Thing.”

My skin is brown, my manner tough,

I’ll kill the first mother I see.

My life has been rough.

I’m awfully bitter these days

Because my parents were slaves.

My name is “Peaches.”

“And are you ‘Peaches?’” the visitor asks.

“I played the boogie at three and gave concerts at twelve.”

She had begun studying at seven and by twelve she was seriously committed to music.

“There was a white woman who had money, she heard about me. There was another white woman who was a music teacher. The two of them got together and did a job for me.”

Her even teeth show in a half-grin.

“And on me.”

The physical beauty of the woman comes across obliquely. Each feature is realized separately. Her large eyes astonish by flashing abruptly and then just as quickly become hidden again. The full, sensuous mouth relaxes in joy, opens wide in laughter and curves downward in anger. The high cheekbones display a shade of brown seen in hand-rubbed African masks. Separately the features are even and pleasurable, but together they for a piece at once strange and alluring.

Nina Simone rep represents the eternal artistic enigma. Her personality contains contradictions of gigantic proportions. She is that consummate performer who practices and sharpness, honing her craft to a piercing point. But in personal appearances she displays an aura of considered apathy. She has woven into her work all the soul-learned truths of pain and joy, yet she is known by many to be unsocial and ungiving in personal contact.

Nina Simone is able to stand upon a shadowed stage, take in all the light and then return that luminescence to her audience in opulent, pulsating rays. At other times and with no seeming reluctance she rejects the audience, rejects their physical fact, rejects their loyalty, rejects their devotion.

What formed this puzzle? What further convolutes this complexity?

“America!”

So Nina Simone says, and her inflection carries centuries of oppression and deferred dreams.

“America is itself a contradiction.” Her sinewy fingers knit dark patterns in the air as she explains that history, Black history, lives for her in the urgency of today, the past being the very alive parent of the future.

A listener, enraptured, is reluctant to interrupt this voice that has whispered “love” into thousands of ears and shouted “revolution” into the hearts of millions.

But what happened, Miss Simone? Specifically, what happened to your big eyes that quickly veil to hide the loneliness? To your voice, that has so little tenderness, yet overflows with your commitment to the battle of Life? What happened to you?

“At three I played boogie.”

The baby fingers strain to touch the eight-note chords and walk up and down the keyboard in tuneful repetitions. “My mother didn’t like it (her mother was a minister), but Daddy let me play the worldly music until he knew Mama was on her way home. Then he’d say, ‘Your mama’s coming; you better save that for the next time.’” Remembering, her eyes dance in childish glee and a mischievous grin darts over her features.

“My early joys were mixed with fear. The church where I spent most of my time spilled over with music and revival. Joy danced around the walls as lively as children and music was the air we breathed and the water we drank. To watch the people in church meet and greet their God was liking watching a reunion between old friends.

“But at the same time I felt left out. Included in the general happiness but left out from the deeper secrets. I was afraid when my mother spoke in tongues. Or when she became silent. Especially when she became silent and went into her private place. I feared that the very thing that provided me with joy could also bring about my alienation.”

The quite, wise face of her mother – Mrs. Waymon – gazes down from a photograph on the mangel.

“That’s my mother, folks. That’s that lady. A great woman.”

Her acceptance wells with pride.

“I had my piano, my parents, my people, my church. The electricity of religion. I had my joys.”

The last is said simply, with the famous voice sounding nearly ordinary.

“Then at seven I began to study. Without willingness and probably consciousness, I traversed two worlds, two cities, two customs, two states of mind, each week. From the Black town with its easy rhythms, its smiling and familiar faces, its well-known sights and scents, to the bordered and tight, frightened and frightening ash-pale face of white Asheville. The mannerisms of my piano teacher and her values had to influence me. I was a baby bombarded by a weight heavier than most children could bear, and more that I could analyze at the time.”

Was any joy there? Any compensation?

“Yes, some. I always had the piano. In either world. I began to understand something about what is called ‘classical music.’ Its structure, its points of convergence. Its reason. And that was good.”

Did the white music have food for your soul?

“No.” A pause. “No, and yet, yes. Bach was a revelation because of his perfect form. His form was complete.”

With this she sits forward, preparing her body to instruct her listener.

“See, his form is like blues and it demands tremendous technique.”

Her shoulders and arms remember their position and they hunch softly as if to help the fingers play.

“Bach’s music is structured like a good piece of architecture. And so are the blues.”

She continues, and she is happy to be talking on this subject to an interested listener:

“You can invert a section of Bach’s music four times, five times, and each way it’s perfect. It’s like saying four times three are twelve and three time four are twelve and twelve divided by three is four. Well, you can do the same with a blues. Use the same notes, triple them and you have one feeling, change the lyrics and you have another, if you like. Invert them and you have something else, but it’s always the same.”

She leans back and rests on her explanation.

“Both of them represent perfect structure.”

At this point a request from eight-year-old Lisa halts Miss Simone’s lecture on Bach, blues and structure.

“Mother, may I visit a friend?”

A pretty, confident child – she is any young girl seeking permission from a doting parent.

“Mother, may I visit a friend?”

But the doting parent is also Nina Simone, the disbelieving and untrusting.

“Where is Sam?” (He is Miss Simone’s brother and constant companion.)

“He’s gone to the bank.” She is still little-girl sure.

Nina looks directly into her daughter’s eyes, “Then you can’t go. Wait. He must know where you are. Wait until your uncle returns.” Her refusal is born of, and couched in, love. The child senses this and leaves the room.

Nina returns to her search, mentally flipping the leaves of a youthful memory book. The sense of quest hangs shadow like about her, more tangible than her give name, Eunice, and more discernible than her birthplace, Tryon, North Carolina.

“Beyond my family, my church and my music I had the good luck to find loving friendships. It was good luck because at about the same time I started giving concerts.”

In the tenderized light of southern Sunday afternoons Eunice Waymon, pre-teenager and child wonder, reached for and often found the finger extensions to bring to life the complex rhythms of Chopin. (She says he represents the technique of Bach mixed with his own romantic soul.)

Will you imagine Eunice, in budding adolescence, offering an audience of Black bourgeoisie a scented program of Chopin, Bach, Scarlatti and Haydn?

See here, now, how the teacher ladies have exchanged the chalk dust of the school blackboard for the talcum powder of distance and distinction. Watch the weekday maids who always knew they were even better than their pretensions. Notice the Black men – morticians, preachers, teachers, and farmers – who, resigned to their stations in quiet dignity, enjoy the afternoons when this Black child brings them a diff of the white man’s magic.

(It was probably thought that since all men live by magic and since the white man lives better than the Black man, his magic must be more powerful.)

But how did Eunice Waymon, protected by the customs and comforts of the Black South, emerge as today’s brilliant, obsidian gem, Nina Simone?

“I found a youthful love and lost it. That was the turning point. I lost love and found a career.”

Her longing stares from heavy eyes.

But, Miss Simone, you are idolized, even loved, by millions now.

“To me, I’m a long way from compensating for what I gave up.”

The life pattern of this mysterious woman begins to rise, Braille-like, under the fingertips. During five slow, Southern years an adolescent crush developed into young, trusting love. This relationship was sanctioned and smiled upon by the Black community.

“When I was seventeen I left my love to go North and study. I had gone to the Juilliard School, in New York City, for a summer’s course, and at seventeen I went back to compete for a scholarship.” Pause “I was not accepted.”

An emptiness yawns beneath the conversation, menacing.

Why were you refused? Is there blame? Yours? Mine? Whose?

“I wasn’t as trained as I had been led to believe. Curtis in Philadelphia also turned me down. Oberlin offered me a scholarship.”

A hard slash of laughter leaps out and whips the air. “But I was too stupid to accept it. I thought it beneath my talents. Had I gone, I would have polished my technique for a year and then I could have gone on to Juilliard.”

Is that all there is?

A direct look. “My rejection could have been occasioned in part by racial prejudice. In this country, how can you tell?”

Indeed.

“Then I lived for a while with a preacher lady in Harlem, a friend of my mother’s, and took private lessons.”

A while?

“Four or five years. Studying, opening the way to deeper understanding.”

Was there joy? Was there a feeling of belonging in Harlem?

“I was lonely all the time. In leaving home I lost my love and I had found nothing to take its place, even partially. I was young, innocent and wounded, and in that vulnerable state I dared the jungle of New York City.”

Her face begins to close into itself, masking thoughts and emotions much as a Japanese fan folds in upon itself.

“When my family moved to Philadelphia I lived with them. I worked. I had to support my family, didn’t I?”

It is not a question. During this period her work schedule was supplemented by more classical training. She had been accepted at Philadelphia’s Curtis Institute of Music, and her piano studies continued for four and half years.

“I was a nurse’s aide in Langhorne, Pennsylvania, and a helper in the dark room of a camera shop. Then my ‘big break’ came. I went to work in a vocal studio accompanying aspiring young, white singers. I made seventy-five scents an hour.

“But that wasn’t all I made. I was a classical pianist. I was trained. So I opened a storefront studio to teach classical piano.

“All told, with my salary from the vocal studio and the moneys from private students I was able to clear around forty-five dollars weekly.”

Here a big laugh wraps round her listener, and we share the endearing absurdity of it all.

“Agents appeared at the vocal studio, offering jobs to the white singers. Jobs in Atlantic City that paid ninety dollars a week. Who had ever heard of so much money? During my second year in the studio I approached one of the agents about getting me a job. My first night’s work was in an Irish bar. Now, picture this. I had never been in a saloon. In our house, as a child we didn’t even have a record player. Even so, I had heard and loved the music of Ivory Joe Hunter and Buddy Johnson; Marian Anderson had been my idol. And here I was, dressed in a pink tiered chiffon dress, playing piano in an Irish bar.”

The tale beings to wind up, marbleizing heavy comedy, light drama.

“The piano was bad, and I told the owner. Drunks were loud in the back, so I tried to hush them by playing Rachmaninoff. I knew nothing about sets, and when I was informed that I was to play forty-five minutes and have fifteen minutes off, I agreed. After all, I’d been playing and practicing seven hours daily most of my life.”

What about the singing? one asks. That voice – from which corner of your existence did it grow?

“I was asked to sing, and so I sang the songs I had learned accompanying the white singers. I had a small voice, and the sense not to push it. I began to innovate.”

Wasn’t that good? Wasn’t that freedom?

“I loved my work. It was a chance to express the music that had been piling up inside.”

College students began to hear of her, and they soon filled the Irish bar. For three summers they followed her devotedly, and insisted on silence form their fellow patrons in the gloomy taverns of Atlantic City. When a New York agent suggested New York City, she had been cushioned by the adoration of a cult and was self-assured by mastery of her craft. She was ready.

Her first record, “I Loves You, Porgy,” was a smash; the cult broadened; her private search for truth deepened.

Dick the Black experience press down on your fingers, forcing those peculiar Simone harmonies from the keys?

“No Black person can be unaware of the climate in the United States. But during my early years I was no more aware than most. My sense of responsibility unfolded slowly. Slowly.”

Her lithe body becomes taut and assumes an Indonesian dance position.

“Then the four babies were murdered in the church. For Black girls. I wrote – or, better, ‘Mississippi Goddam’ wrote itself through me. I had to say something – express or explode.”

Maybe both?

“Yes, both.”

Were the children who were bombed in the church also the seeds of your scalding composition “Four Women”?

Quietly: “I guess they were. They came to me while I was on an airplane. I wrote it and kept it to myself for a year before I was ready to share it. I had to make sure I was saying a whole truth.”

What about the Black artist in America generally? This woman accepts no generalities. She chooses to be particular, personal.

“At this time I must stretch to reach my fullest potential. I must address myself to the needs of my people…my people need inspiration.”

As she settles into her credo her body relaxes with the assurance of right direction.

“It’s not enough to be a ‘great artist.’ If I have the power to convince, I am bound to use it…”

She gives her audience a seldom-seen, gentle smile.

“White artists can indulge in laziness, can afford to be lazy. Black artists can’t. That’s all.”

Life has left keloidal scars on her voice, and wells of angry tears lie beneath each spoken word. Here lies innocence betrayed, and the keening that is heard is a dirge for hope abused.

She is loved or feared, adored or disliked, but few who have met her music or glimpsed her soul react with moderation. She is an extremist, extremely realized.

THE END